From A Canoe Is The Best Way To See Wildlife In The Amazon

Erin Van Der Meer is a formerly Sydney-based writer who…

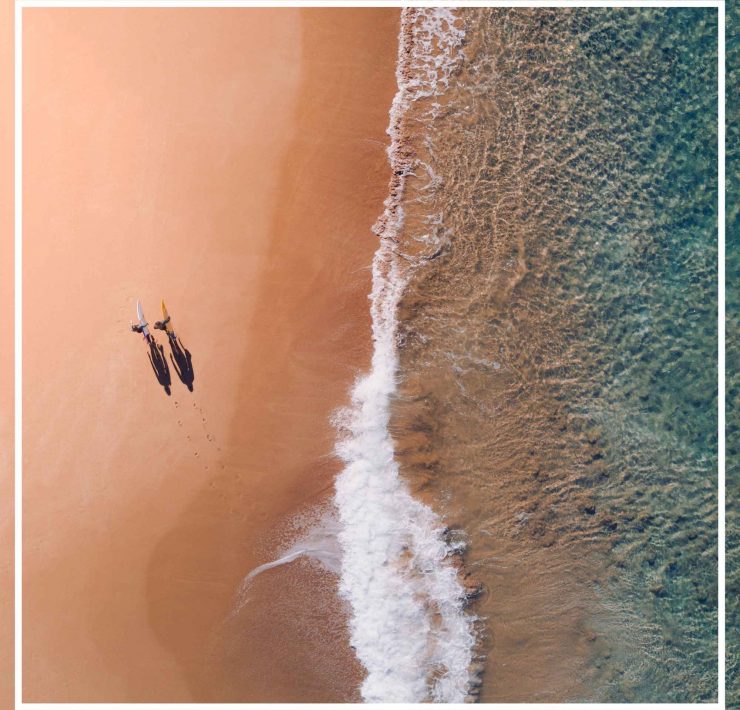

As we pushed off the riverbank and joined the current of brown water flowing into the jungle, I wondered if it was crazy to spend four days in a canoe in the Amazon.

While backpacking around Peru, I heard about a way to explore the Amazon far from the mass tourism and high prices of places like Iquitos. Looking for an adventure – and importantly a budget-friendly one – we were sold.

After several long bus rides from Lima we arrived in Yurimaguas, a remote town on the edge of the rainforest (we went the long, cheap way, but you can fly to Tarapoto then take a two-hour bus), and booked a four-day, three-night canoe trip with Huayruro Tours Lagunas.

At sunrise the next day we boarded a fast boat and, six hours later, we were in the small town of Lagunas. We met our guides Rainer and Tachi, and the five of us soon climbed into the canoe and set off for four days in Peru’s Pacaya Samiria Reserve.

Day #1

The more-than 20,000-square-kilometre Pacaya Samiria Reserve is home to more than 1000 species. But, as we floated along, it felt like we were the ones being watched.

The tranquil quiet was broken by the sound of leaves rustling, a twig snapping, a curious ‘plop’ like something jumping into the water. But, other than the insects that loop-de-looped around our heads like tiny stunt planes, I couldn’t see anything but dense, green jungle. It felt as though the Amazon’s inhabitants were hiding, waiting for us to pass so they could resume their raucous jungle party.

But, as Rainer rowed our canoe gently along with graceful strokes, he assured us we’d see plenty of animals. As if on cue, a family of about 10 monkeys came crashing through the trees, swinging from branch to branch, a baby clinging to its mother’s back.

It wasn’t long before Rainer stopped rowing and pointed upwards again, this time at a grey, black and white eagle perched on the highest branch of a tree.

“This is a very rare sighting,” he said. “They hunt more in the rain because they eat monkeys, and monkeys sleep when it rains.” I got chills thinking of the baby on its mother’s back.

Just before sunset we arrived at another hut on stilts on the riverbank, our home for the night.

The jungle had been tranquil during the day but, at night, it really came alive. In the distance a monkey screamed as something scurried on the dirt floor below the hut. The frogs took centre stage, harmonising in a deep baritone, lulling us to sleep.

Day #2

At sunrise the frogs made way for the birds, who chirped and squawked noisily on their morning hunt for food. A mist hung over the river. Fish flopped around in the water, making concentric circles on the surface.

After breakfast, we set off in the canoe. I felt more at ease than the day before, and could appreciate the tranquillity of the flowing river, the sunlight filtering through the rainforest canopy, the long green tendrils that hung down and brushed our faces.

The first sighting of the day was a pair of lobo del rios, or river otters. We only just saw their brown heads bobbing in the water up ahead as they dashed from one side of the river to the other and disappeared into the mangroves.

We also saw a few sloths hanging high up in the tree branches. Rainer told us they’re called oso perezosos (“lazy bears”) in Spanish.

In the afternoon, we had another rare sighting – other people. A guide and two tourists were heading in the opposite direction, the first of only two times we would pass other travellers. I noticed when I filled out the sign-in book before heading into the jungle there had only been 20 visitors to this part of the reserve in 10 days.

When we pulled into another hut in the afternoon, Rainer told us this was as far as we would go into the Amazon. Tomorrow, we would go back the way we came – but not before we saw the reserve’s famous pink river dolphins.

At a cove 20 minutes downstream, Rainer stopped rowing and we waited in silence until we glimpsed a fin breaching the water’s surface. Then another, and another. A pod of 20 or more pink river dolphins surfaced for every few to reveal their long noses and shiny pink-grey skin, before disappearing again.

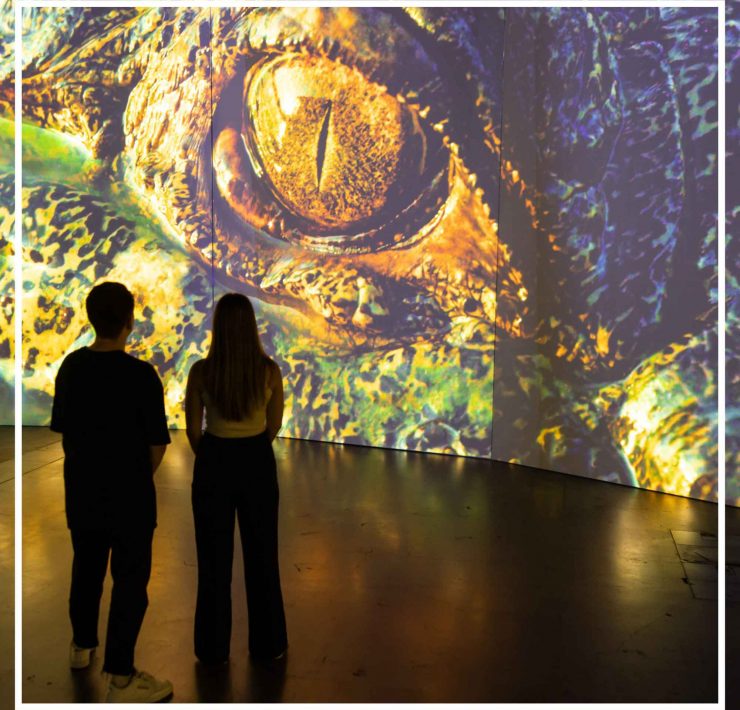

Back at camp, Rainer told us we’d be going on a night expedition to see crocodiles. He also assured us they were only small and couldn’t hurt us.

After dinner, we climbed into the canoe, armed with flashlights, and set off into the dark. It was pitch black except for the astonishingly visible stars. We sat in silence for a few minutes, then Rainer shone a torch into the mangroves, where little crocodiles – maybe the size of a loaf of bread – began to scatter.

The light of the torch just caught their scaled bodies – black on top, white underneath – as they splashed wildly into the river and out of sight. Rainer switched off the torch and began to row back to camp. I looked for their little eyes glowing in the dark, watching us, but there was no light but the stars.

(Lead image: Alfonso Zavala via PROMPERU)

[qantas_widget code=LIM]Check out Qantas flights to Lima.[/qantas_widget]Erin Van Der Meer is a formerly Sydney-based writer who decided the whole desk job thing just didn’t allow enough time for travel. So she quit said job, bought a flight to Mexico and has been living out of a suitcase ever since. Keep track of her latest adventures on Instagram or Twitter.