Karijini: The WA Playground That’s More Theme Park Than National Park

After spending years as a music journalist and beer-taster, Alexis…

“Don’t forget to scream,” a voice behind me calls out. I’m sitting in a small pool of water and the striped walls of Knox Gorge rise some hundred metres above me on either side, a sliver of sky barely visible between them.

The banded iron is shiny and smooth from eons of water rushing through and the gorge is maybe a metre wide at this point. Beneath me, the floor slopes off in a natural waterslide and, as I push off the sides, I quickly gather momentum until the rock beneath me disappears and I tumble 4m down into a sunlit turquoise pool. I don’t forget to scream.

Until about 10 years ago, this area was open to the public, but a series of accidents led the park to restrict entry. Now, it’s only accessible as part of a tour (which will kick back up in 2021) and this is just the beginning of our day-long adventure.

We abseil down the next waterfall before emerging into the much wider Red Canyon, where the abundant sunlight supports a wide range of flora. A flash of purple indicates a patch of late-flowering royal mulla mulla, while tenacious fig trees jut out of the canyon walls at odd angles, their roots thrust deep into the rock.

Above them, the layered canyon walls rise dramatically, but there’s no need to crane my neck for this view. I can take it all in from my vantage point laying flat on an inner tube as I slowly float down the canyon, enjoying the peaceful interlude on an action-packed day.

It’s a great time to get to know the rest of the group, a geographically diverse collection of backpackers and young professionals, as well as our guide, Josh. A former schoolteacher who was unable to resist the call of the wild, he fell in love with Karijini on a family trip at age 12 and was always looking for an excuse to return.

Despite its remote location deep in the Pilbara in Australia’s vast northwest, he eventually made it back and it’s obvious why the place had such a great impact on him. It’s difficult to overstate the grandeur of these deep fissures that cut through the burnt orange rock, the perfect setting for an action-packed adventure or for a spot of quiet contemplation.

Only a fraction of the park’s canyons have marked walking trails, but each one is spectacular in its own right. Dramatic folds in the rock at Hamersley Gorge provide a hands-on geology lesson while a narrow, Siq-like opening in Weano Gorge conjures visions of Indiana Jones before the passage opens out into a spectacular circular swimming hole at Handrail Pool.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Donna || Bucko || Tex || Tilly (@travelling.buckinghams) on

At Fern Pool, a waterfall cascades into a stunning shaded pond that swimmers are encouraged to enter quietly, announcing their presence to the resident spirit by taking in a mouthful of water and spitting it out. It’s a place of great cultural significance to local Indigenous groups and a profoundly peaceful spot.

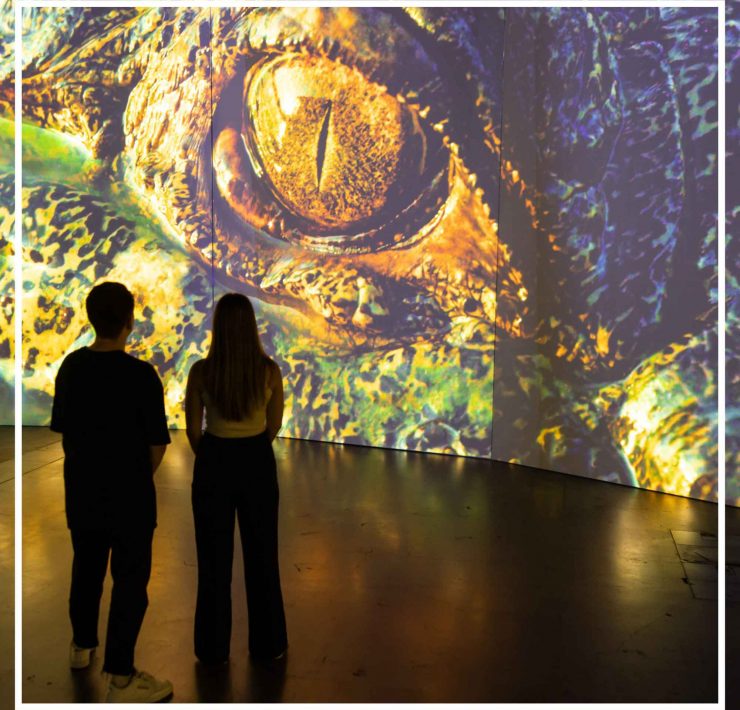

It’s still shared with the 400,000 other annual visitors to the park but, for most of our day-long adventure, we’re entirely alone. At “the centre of the earth”, we emerge into a small chamber in the rock, surrounded by the compressed bed of a two-a-half-billion-year-old sea.

The shade offers respite from the heat of the sun, and the only sound is the trickle of water from a small stream. A small Pilbara rock monitor with a pinkish hue watches us cautiously before it’s time to move on.

Climbing up a waterfall and then scrambling, swimming and rock climbing up, we make our way back up to the surface.

Then it’s back to the Karijini Eco Retreat, where the day ends and I have a comfortable bed waiting for me. My accommodation is a tent in the sense that it has canvas walls, but with a raised floor, front deck and an en suite, it’s certainly a bit more luxurious than the ones I’m used to.

It’s set in the middle of beautiful bushland, and my solar-powered shower looks out over deep red termite mounds and snappy gums as the sun slowly sets and adds an orange tinge to the landscape.

In the next tent, my neighbours are discussing their dinner plans but their voices are soon lost in the calls of crickets and the nocturnal birds they’re hiding from. Tiny frogs that have colonised my en suite add their voices to this evening chorus and I find myself drifting off to sleep – after all, there are a lot more canyons to explore tomorrow.

When to go

Karijini National Park is open year-round, but visitors in summer have to contend with high temperatures and the risk of flash foods. The cooler months from May to September are the ideal time to visit.

(Lead image: Andrew Fidler ‘FidlerFoto’ / Flickr)

After spending years as a music journalist and beer-taster, Alexis Buxton-Collins now travels the world searching for new adventures to write about, from navigating the Alps with Austria's last nomadic shepherd to hiking through the Central American rainforest in search of ancient Mayan pyramids.